Raila Odinga’s bid for the African Union Commission (AUC) chairmanship has reinforced a crucial reality: Kenya’s diplomatic influence in Africa is on the rise. Under the leadership of Musalia Mudavadi and Noordin Haji, Kenya has made significant strides in navigating the continent’s complex geopolitical landscape, demonstrating its growing clout despite deep-seated regional, religious, and linguistic divisions.

Many assume that success in the AUC elections hinges solely on lobbying, overlooking the entrenched power dynamics that shape the process. The AU has long been a battleground where Francophone versus Anglophone, Muslim-majority versus Christian-majority, and North versus Sub-Saharan Africa interests collide. Historically, the AUC chairpersonship has never been awarded on merit alone but has been determined through strategic regional and confessional alliances. Expecting Kenya’s diplomatic team to dismantle this entrenched system in one attempt misinterprets the realities of continental politics.

Religious and linguistic alliances continue to shape AU elections. Francophone Africa, largely Muslim-majority, has historically supported candidates aligned with its interests, often at the expense of Anglophone Christian candidates. This played a key role in Raila Odinga’s campaign, much as it did in Amina Mohamed’s unsuccessful bid during Uhuru Kenyatta’s administration. However, unlike Amina’s campaign, which saw Kenya struggle to build traction, Mudavadi and Haji’s diplomatic groundwork ensured Raila’s bid gained significant ground, reflecting Kenya’s increased leverage on the continental stage.

Despite facing opposition from Muslim-majority states keen on maintaining their influence, Kenya secured 34 pre-summit endorsements—an impressive improvement from previous attempts. While the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) quietly lobbied against Raila’s bid, and the Sahelian bloc, led by junta governments with growing ties to the Arab League, remained skeptical, Kenya’s strategy demonstrated an ability to navigate these obstacles more effectively than in the past. Unlike Amina’s campaign, which saw Kenya largely isolated after the first voting round, Raila’s bid showcased a stronger, more resilient diplomatic approach.

Beyond intra-African divisions, Western powers continue to manipulate AU elections to serve their geopolitical interests. The AU remains an arena where the US, Gulf states, the European Union, China, and former colonial powers exert influence through financial incentives and strategic partnerships. France, for example, still wields considerable sway over Francophone Africa, ensuring that candidates from its sphere of influence secure key AU positions. Meanwhile, Gulf states like Qatar and Saudi Arabia have increased their involvement in African politics, backing candidates aligned with their broader strategic goals.

For Kenya to maintain and expand its influence, it must develop a long-term strategy to counterbalance these external pressures. The progress seen in Raila’s bid compared to Amina’s underscores Kenya’s improving ability to maneuver these geopolitical complexities. While global actors continue to shape the AU’s political landscape, Kenya’s growing ability to rally African support marks a crucial shift in its diplomatic positioning.

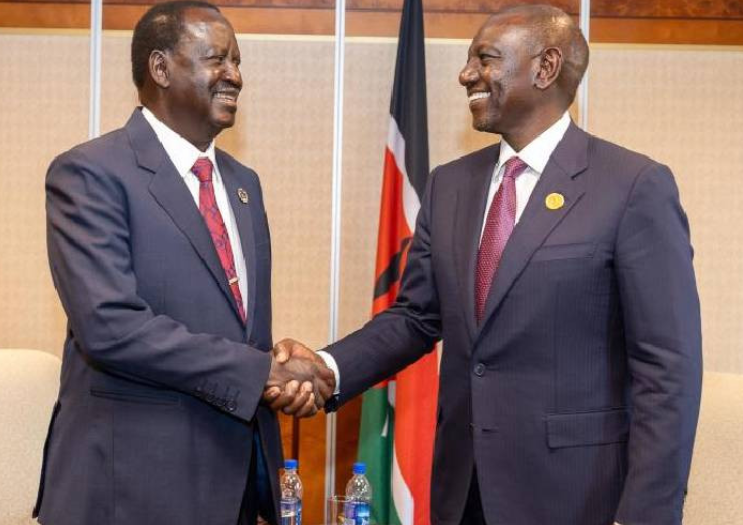

Mudavadi and Haji played distinct but interconnected roles in this process. As Prime Cabinet Secretary and Foreign Affairs CS, Mudavadi anchored Kenya’s foreign policy through strategic partnerships and historical alliances. Meanwhile, Haji, as the National Intelligence Service (NIS) Director General, focused on aligning Kenya’s continental engagements with national security imperatives, particularly amid rising extremist threats and shifting geopolitical tides in the Horn of Africa.

Although Raila’s bid did not result in outright victory, it positioned Kenya as a formidable contender in African diplomacy. The alliances and goodwill secured during this campaign are assets for future continental engagements—an outcome that Amina’s campaign did not achieve at the same scale. Kenya’s efforts are no longer fading into diplomatic obscurity; instead, the country’s rising credibility on the continental stage signals a new era of influence.

However, Kenya’s AUC bid also highlights deeper dysfunctions within the AU itself. The organization remains plagued by regionalism, religious factionalism, and foreign interference. Instead of blaming envoys, African nations must confront uncomfortable truths: first, the AU’s electoral process prioritizes regional rotation over meritocracy; second, external actors continue to exploit Africa’s divisions for their own gain; and third, religious and linguistic alliances still dictate key decisions, often at the expense of the continent’s best interests.

To strengthen its position in African politics, Kenya must invest in sustained, year-round coalition-building rather than the episodic diplomatic engagements of the past. Moreover, Africa as a whole must address the growing sectarian and ideological divides that hinder continental unity. Until these fractures are resolved, no amount of diplomatic maneuvering will be sufficient to deliver true cohesion and progress across the continent.